Airflow 3 and Airflow AI SDK in Action - Analyzing League of Legends

Learn Key Airflow 3 and AI Features Through a Practical League of Legends Data Project

You’re standing in Ancient Egypt, around 250 years before the start of our modern calendar. As your eyes adjust to the warm light shining through high windows, you find yourself in the Great Library of Alexandria. What you see is overwhelming: shelves stretch in every direction, holding nearly half a million scrolls. The air is thick with the scent of papyrus and you’re searching for writings about astronomy. You hear the quite rustling of Callimachus, the library’s most celebrated scholar, working on the solution for your problem.

He revolutionized information retrieval by creating the Pinakes - the world’s first library catalog. Instead of organizing scrolls merely by author or title, he pioneered a system that categorized works by their subject matter and content, enabling scholars to discover related works they might never have found through simple alphabetical browsing.

Illustration of Callimachus, source: generated with DALL-E 3

Illustration of Callimachus, source: generated with DALL-E 3

Over 2,000 years later, we face a similar challenge. In the digital archives of Netflix’s early days, engineers worked on their own Alexandria-scale problem. Their movie recommendation system, built on simple rating matches, struggled to capture the essence of what makes films truly similar. A comedy about a wedding might share more DNA with a romantic drama than another comedy about sports, yet traditional categorization methods - much like organizing scrolls by their physical attributes - missed these subtle connections. This challenge of semantic understanding - capturing the true meaning and similarity between items - remains at the heart of modern search and recommendation systems.

Today, we stand at an interesting crossroad. The evolution of vector search solutions, due to their prominent use in Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems, promises to solve these semantic matching problems, but with a catch: most solutions demand complex infrastructure, significant resources, and careful maintenance. However, for some cases, there is a pragmatic answer to this complexity: DuckDB’s Vector Similarity Search (VSS) extension.

In this guide, we’ll build a movie recommendation engine that could have solved Netflix’s early challenges, using modern tools that fit in your laptop’s memory. By combining DuckDB’s VSS extension with Gemini’s embedding capabilities, we’ll create a system that understands the essence of movies, not just their metadata. Whether you’re building the next big recommendation engine or simply want to understand vector search better, this practical journey will equip you with the knowledge to tackle semantic search challenges in your own projects.

Before we dive into similarity search, let’s understand how we convert movie descriptions into numbers that computers can understand. This is where embeddings come in.

Embeddings work by converting text, image, and video into arrays of floating point numbers, called vectors. These vectors are designed to capture the meaning of the text, images, and videos. The length of the embedding array is called the vector’s dimensionality. For example, one passage of text might be represented by a vector containing hundreds of dimensions.

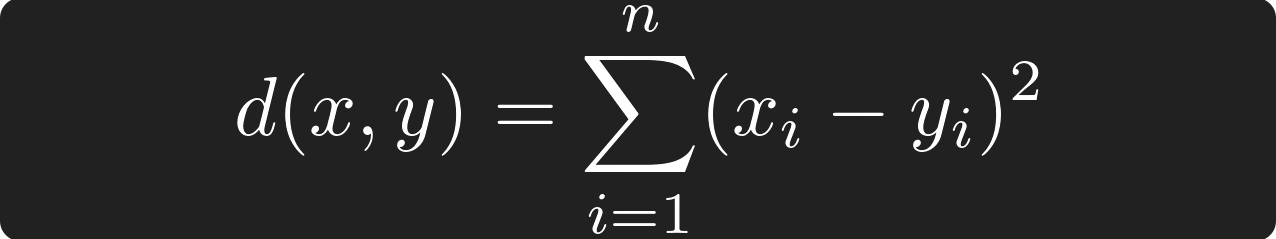

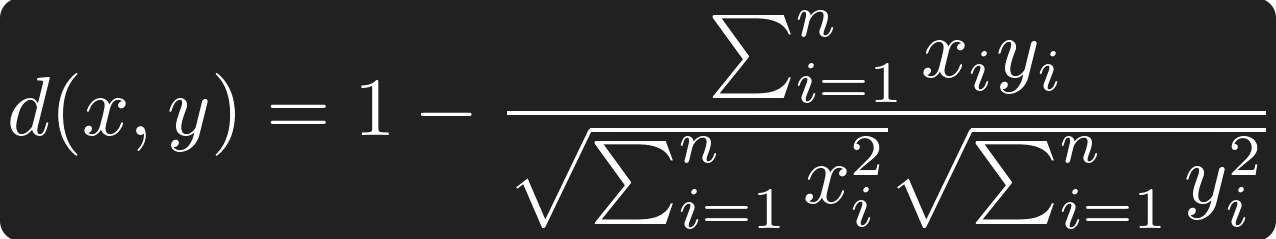

Once we have these numerical vectors, we need ways to measure how close or similar they are.

DuckDB introduced the ARRAY data type in v0.10.0, which stores fixed-sized lists, to complement the variable-size LIST data type.

They also added a couple of distance metric functions for this new ARRAY type: array_distance, array_negative_inner_product and array_cosine_distance. With these distance functions, similarity can be measured:

Euclidean Distance, source: by author

Euclidean Distance, source: by author

Cosine Distance, source: by author

Cosine Distance, source: by author

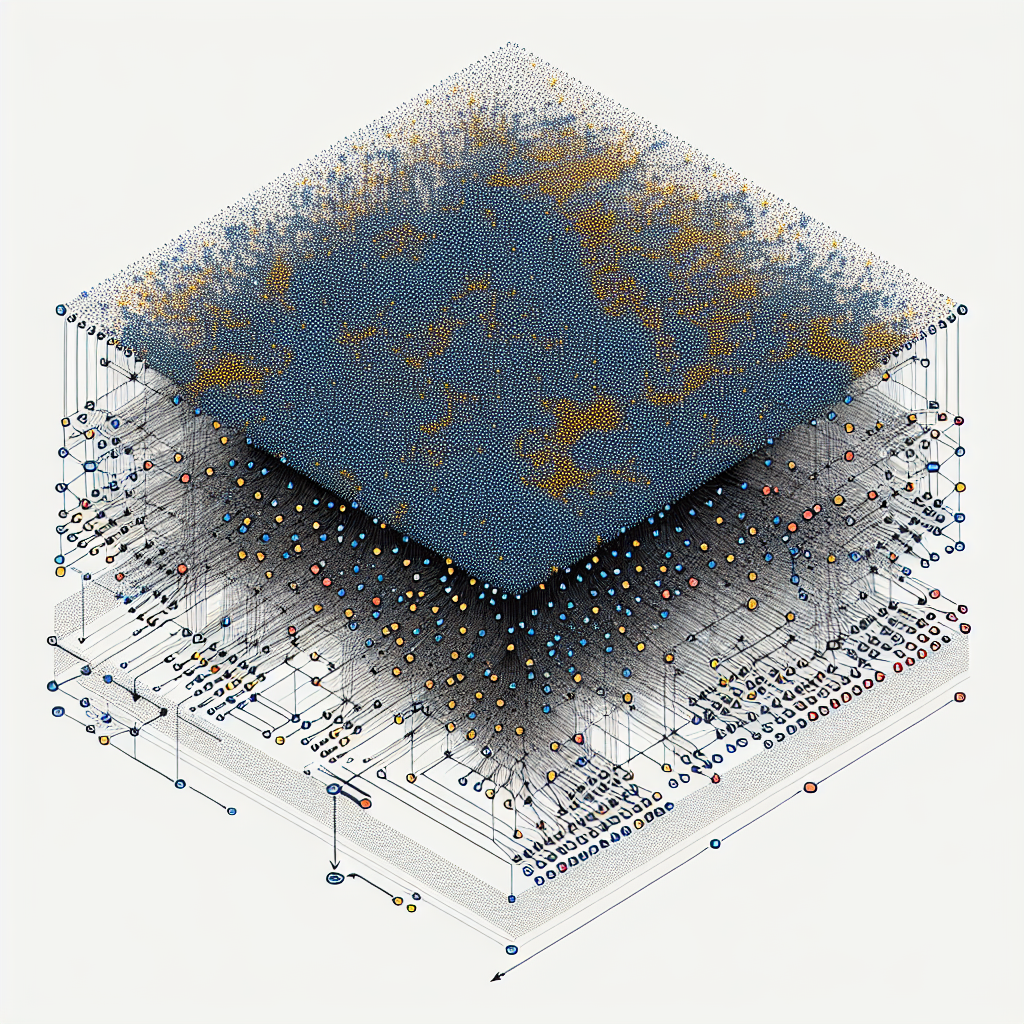

DuckDB’s VSS extension then added support for Hierarchical Navigable Small Worlds (HNSW) indexes to accelerate vector similarity search.

Let’s get an idea how the HNSW index works. Imagine you’re in New York City trying to find a World of Warcraft player who also teaches quantum physics. Here’s how different search approaches would work:

Stop every single person in NYC and ask if they match your criteria.

Think of it like a cleverly organized social network with different levels of connection:

Level 3 (Top Level) - Global Connections

Level 2 (Mid Level) - District Connections

Level 1 (Ground Level) - Local Connections

HNSW visualization, source: generated with DALL-E 3

HNSW visualization, source: generated with DALL-E 3

The search starts at the top level, quickly identifies promising areas, and drills down efficiently. For 1 million candidates, you’ll check about 20 instead of all million, while maintaining 95–99% accuracy.

duckdb ≥ 1.1.3, httpx, google-cloud-aiplatform

from typing import List, Dict

import duckdb

import httpx

from google.cloud import aiplatform

from vertexai.language_models import TextEmbeddingModel

tmdb_api_key: str = 'your-tmdb-api-key'

credentials = service_account.Credentials.from_service_account_file('your-sa.json')

aiplatform.init(project='your-project', location='us-central1', credentials=credentials)We fetch movie data from the TMDB API using httpx. Also, we allow to specify a minimum average voting score and count, to reduce the dataset to more famous movies.

def _get_movies(page: int, vote_avg_min: float, vote_count_min: float) -> List[Dict]:

""" Fetch movies from TMDB API """

response = httpx.get('https://api.themoviedb.org/3/discover/movie', headers={

'Authorization': f'Bearer {tmdb_api_key}'

}, params={

'sort_by': 'popularity.desc',

'include_adult': 'false',

'include_video': 'false',

'language': 'en-US',

'with_original_language': 'en',

'vote_average.gte': vote_avg_min,

'vote_count.gte': vote_count_min,

'page': page

})

response.raise_for_status() # Raise an error for bad responses

return response.json()['results']

def get_movies(pages: int, vote_avg_min: float, vote_count_min: float) -> List[Dict]:

""" Generator to yield movie data from multiple pages """

for page in range(1, pages + 1):

yield from _get_movies(page, vote_avg_min, vote_count_min)We use Gemini’s text-embedding-004 model to generate embeddings and set the vector dimensionality to 256.

Note: The dimension size (256) must match in both embedding generation and DuckDB table creation.

def embed_text(texts: List[str]) -> List[List[float]]:

""" Generate embeddings for a list of texts using Gemini """

model = TextEmbeddingModel.from_pretrained('text-embedding-004')

inputs = [TextEmbeddingInput(text, 'RETRIEVAL_DOCUMENT') for text in texts]

embeddings = model.get_embeddings(inputs, output_dimensionality=256)

return [embedding.values for embedding in embeddings]

# Fetch movies from TMDB API and generate embeddings

movie_data = list(get_movies(3, 6.0, 1000))

movies_for_embedding = [(movie['id'], movie['title'], movie['overview']) for movie in movie_data]

embeddings = embed_text([overview for _, _, overview in movies_for_embedding])As a next step, we install and load the VSS extension in DuckDB, and enable persistence. This allows us to store the embeddings in a database file.

INSTALL vss;

LOAD vss;

SET hnsw_enable_experimental_persistence = true;We then create the table, using the same dimensionality as before.

CREATE TABLE movies_vectors (

id INTEGER,

title VARCHAR,

vector FLOAT[256]

)After inserting the embeddings, we create a HNSW index on the vector column in order to speed up vector similarity search.

CREATE INDEX movies_vector_index ON movies_vectors USING HNSW (vector)We then prepare a function, that takes a movie description as input. This is the search query from the user. We also create an embedding vector based on this input. Finally, we use a DuckDB distance function to get similar movies.

SELECT title

FROM movies_vectors

ORDER BY array_distance(vector, array[{vector_array}]::FLOAT[256])

LIMIT 3With that, this is how the DuckDB VSS setup looks like:

# Set up DuckDB with Vector Similarity Search (VSS) Extension and persistence enabled

# See: https://duckdb.org/docs/extensions/vss.html

with duckdb.connect(database='movies.duckdb') as conn:

conn.execute("""

INSTALL vss;

LOAD vss;

SET hnsw_enable_experimental_persistence = true;

""")

conn.execute("""

CREATE TABLE movies_vectors (

id INTEGER,

title VARCHAR,

vector FLOAT[256]

)

""")

# Insert embeddings into DuckDB

conn.executemany("INSERT INTO movies_vectors VALUES (?, ?, ?)", [

(movies_for_embedding[idx][0], movies_for_embedding[idx][1], embedding)

for idx, embedding in enumerate(embeddings) if len(embedding) == 256

])

# Create Hierarchical Navigable Small Worlds (HNSW) Index

conn.execute("CREATE INDEX movies_vector_index ON movies_vectors USING HNSW (vector)")

def search_similar_movies(query: str):

""" Search for movies similar to the given query description """

query_vector = embed_text([query])

vector_array = ', '.join(str(num) for num in query_vector[0])

query = conn.sql(f"""

SELECT title

FROM movies_vectors

ORDER BY array_distance(vector, array[{vector_array}]::FLOAT[256])

LIMIT 3

""")

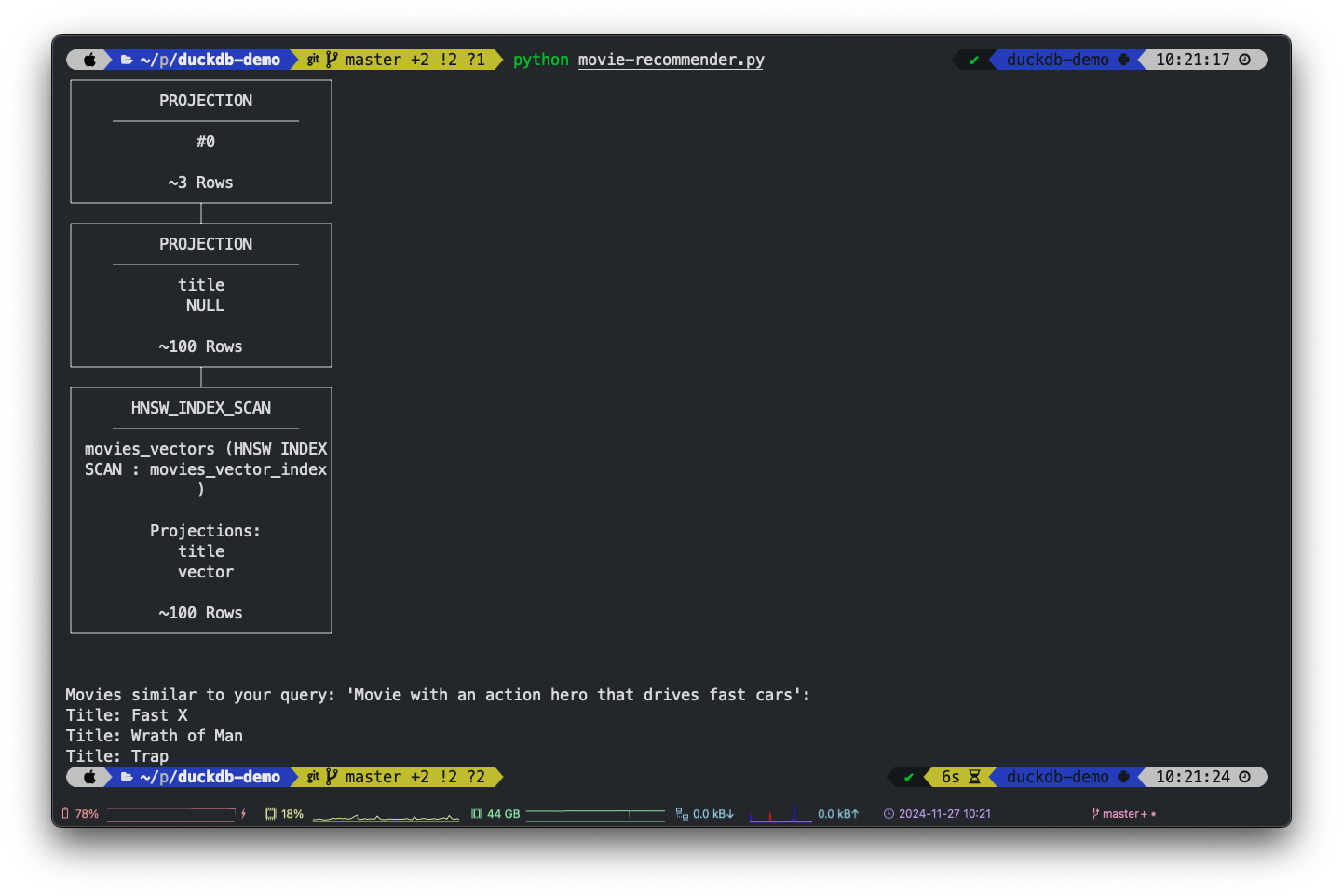

print(query.explain()) # Print the query plan to show the HNSW_INDEX_SCAN node

return query.fetchall()We are not only returning the similarity search result, but also print the query plan with query.explain() to show that the HNSW index is actually used.

Putting everything together, this is the full example:

from typing import List, Dict

import duckdb

import httpx

from google.cloud import aiplatform

from google.oauth2 import service_account

from google.oauth2.service_account import Credentials

from vertexai.language_models import TextEmbeddingModel, TextEmbeddingInput

tmdb_api_key: str = 'your-tmdb-api-key'

credentials = service_account.Credentials.from_service_account_file('your-sa.json')

aiplatform.init(project='your-project', location='us-central1', credentials=credentials)

def _get_movies(page: int, vote_avg_min: float, vote_count_min: float) -> List[Dict]:

""" Fetch movies from TMDB API """

response = httpx.get('https://api.themoviedb.org/3/discover/movie', headers={

'Authorization': f'Bearer {tmdb_api_key}'

}, params={

'sort_by': 'popularity.desc',

'include_adult': 'false',

'include_video': 'false',

'language': 'en-US',

'with_original_language': 'en',

'vote_average.gte': vote_avg_min,

'vote_count.gte': vote_count_min,

'page': page

})

response.raise_for_status() # Raise an error for bad responses

return response.json()['results']

def get_movies(pages: int, vote_avg_min: float, vote_count_min: float) -> List[Dict]:

""" Generator to yield movie data from multiple pages """

for page in range(1, pages + 1):

yield from _get_movies(page, vote_avg_min, vote_count_min)

def embed_text(texts: List[str]) -> List[List[float]]:

""" Generate embeddings for a list of texts using Gemini """

model = TextEmbeddingModel.from_pretrained('text-embedding-004')

inputs = [TextEmbeddingInput(text, 'RETRIEVAL_DOCUMENT') for text in texts]

embeddings = model.get_embeddings(inputs, output_dimensionality=256)

return [embedding.values for embedding in embeddings]

# Fetch movies from TMDB API and generate embeddings

movie_data = list(get_movies(3, 6.0, 1000))

movies_for_embedding = [(movie['id'], movie['title'], movie['overview']) for movie in movie_data]

embeddings = embed_text([overview for _, _, overview in movies_for_embedding])

# Set up DuckDB with Vector Similarity Search (VSS) Extension and persistence enabled

# See: https://duckdb.org/docs/extensions/vss.html

with duckdb.connect(database='movies.duckdb') as conn:

conn.execute("""

INSTALL vss;

LOAD vss;

SET hnsw_enable_experimental_persistence = true;

""")

conn.execute("""

CREATE TABLE movies_vectors (

id INTEGER,

title VARCHAR,

vector FLOAT[256]

)

""")

# Insert embeddings into DuckDB

conn.executemany("INSERT INTO movies_vectors VALUES (?, ?, ?)", [

(movies_for_embedding[idx][0], movies_for_embedding[idx][1], embedding)

for idx, embedding in enumerate(embeddings) if len(embedding) == 256

])

# Create Hierarchical Navigable Small Worlds (HNSW) Index

conn.execute("CREATE INDEX movies_vector_index ON movies_vectors USING HNSW (vector)")

def search_similar_movies(query: str):

""" Search for movies similar to the given query description """

query_vector = embed_text([query])

vector_array = ', '.join(str(num) for num in query_vector[0])

query = conn.sql(f"""

SELECT title

FROM movies_vectors

ORDER BY array_distance(vector, array[{vector_array}]::FLOAT[256])

LIMIT 3

""")

print(query.explain()) # Print the query plan to show the HNSW_INDEX_SCAN node

return query.fetchall()

# Example Search

query_description = 'Movie with an action hero who drives fast cars'

similar_movies = search_similar_movies(query_description)

# Display results

print(f"Movies similar to your query: '{query_description}':")

for movie in similar_movies:

print(f"Title: {movie[0]}")You can search for similar movies using natural language descriptions. For example:

query_description = 'Movie with an action hero who drives fast cars'

similar_movies = search_similar_movies(query_description)The system will:

Movie Recommender demo, source: by author

Movie Recommender demo, source: by author

Remember Callimachus and his Pinakes - sometimes the most elegant solutions are also the simplest. Often the tech industry’s answer to every problem is add more infrastructure. DuckDB VSS reminds us of a timeless truth: you don’t always need distributed systems to solve challenges effectively. Just as the ancient librarian created a groundbreaking system with fundamental principles, we too can tackle modern recommendation challenges with straightforward, efficient tools that get the job done.

Whether you’re building a movie recommendation engine or tackling other semantic search challenges, the principles and techniques demonstrated here provide a solid foundation for your projects. The power of vector similarity search, combined with the simplicity of DuckDB, opens up new possibilities for creating sophisticated search and recommendation systems or Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) systems without the complexity of distributed architectures.